Do I S-S-Stutter?

“W-w-w-what does a H-h-h-h-hess fruck c-carry?” Struggling to get the words out, my seven-year old face turned red and lower jaw quivered uncontrollably.

“W-w-w-what does a H-h-h-h-hess fruck c-carry?” Struggling to get the words out, my seven-year old face turned red and lower jaw quivered uncontrollably.

“What?” my father asked, trying to understand my question.

I exhaled in frustration, dropping my arms to my side. Determined to know the answer, I took a deep breath and continued again, trying to force the words from my mouth, to no avail. Defeated, I went to my room and flicked one of the wheels on my new toy tractor trailer box truck I had received as a Christmas gift and watched it spin. There was a low rumble as the rubber tire spun down.

Later that day my father took us to see our grandmother, which brought new hope of getting my question answered.

“What are you trying to say?” my grandmother asked as she placed a piece of chocolate cake on the table in front of me. I stammered on, but the words were incomprehensible. My grandmother glanced up at my father with a confused look on her face. They went on with their “adult” conversation as if I didn’t matter until my uncle, Jan, came into the room. I loved my uncles. They were always doing something interesting and were happy to include me and my brother. If anybody could understand me, he could.

“Uncle Jan, w-w-w-w-w-what d-does a H-h-h-h-h-h-hess f-f-fruck c-carry?”

“Can you figure out what he’s saying?” my grandmother asked.

Jan immediately understood me. He looked at everybody in disbelief, like it was very obvious and he couldn’t believe nobody else could here it. “He’s asking what does a Hess truck carry.”

“Ohhh,” my grandmother said, dragging out the word to show she understood.

My father gave the obvious answer. “Gasoline.”

My heart sank. How could they think I didn’t know that Hess trucks carried gasoline. I’m not stupid. But all my intelligence was pent up inside my brain. I couldn’t get it out of my mouth. I understood that tanker trucks carried gasoline, but what about the tractor trailer box truck I had with HESS written across its side in big bold letters. What would a gasoline company be hauling inside a box truck? Getting those words out would have been too much effort, so I sulked away and sat on the couch in the living room feeling dejected.

“What’s the matter?” my grandmother asked.

“Nothing,” I whined. Sure, I could say that with no problem at all.

I could hear them talking among themselves as if I wasn’t there. “I guess he was expecting something more exciting,” my grandmother said to my father. They had no idea that my question went much deeper. They probably didn’t know the answer, I told myself.

This challenge haunted me all through school. When teachers asked a question and I knew the answer, I couldn’t speak out and say it. Even when the question was directed at me, I held back from answering, knowing I would have difficulty speaking. I would simply shake my head as if I didn’t know. It became even more problematic when the other kids began teasing me. I pulled back even more, refusing to participate, which caused my grades to drop. I would find myself constantly being pulled out of advanced classes and placed into groups where other children had learning difficulties. Socially, I fit in better and my grades soared, then the school would pull me from there and place me into remedial classes, then back into advanced classes and back again to the special classes. It seemed nobody knew where I belonged.

#Stuttering had a physiological effect on me as well. Grades weren’t entirely related to how much I studied or homework I did. I could work hard and still not do as well when participation was factored in. Working hard didn’t change things. Since lower grades were not as devastating as being teased, I accepted them as a fact of life that could not be helped. It made me not want to try. So I didn’t.

I remember a few times when I did push myself past my comfort zone. One of those times was in jr. high school when my social studies teacher decided to teach the class about videography. I was mesmerized. Next to electronics, this was one of the coolest things I had ever seen. When the teacher asked for a volunteer to participate in creating a video, my heart pounded. I wanted to go up more than anything else, but I knew I couldn’t, so I bit my tongue. Two other students volunteered and I felt terrible inside. Then the teacher asked if anybody had an idea of what they could film. I remembered seeing a trick where a magician said he could cut a hole in a single piece of loose-leaf paper large enough to walk through. When nobody else spoke up, I knew I had to do it. Somehow I mustered up the courage and croaked, “I do.” Nervous, shaking, and stuttering my way through, I managed to perform the trick in front of the cameras and the class. My performance must have been interesting enough to keep my classmates minds off my stuttering because nobody said anything about it. However, I did feel sick afterwards and had a headache which landed me in the nurses office for the rest of the day.

I did it again one day for a little circle of underachievers that met every day in lieu of the standard English class. I was transferred into this #specialNeeds group when I failed to perform in the standard classes. My first assignment in this group was to write a poem and read it in front of the others, something I would never have attempted in front of a regular class. Everybody else had trouble with the assignment but it was easy for me. I was so proud of what I had written, I was actually excited to read it out loud. Even though I knew it would be difficult, I found myself waiting my turn instead of making an excuse to leave the room. Some how I was able to tune everything out as I read. It was the strangest thing. After I finished reading I had no memory of the incident, only a fuzzy recollection that something happened, like a dream that you could barely remember. The other students were so impressed with my poem that they began questioned why I was transferred there in the first place. I guess I impressed the #teacher too. The next day I was back in a standard English class where kids flicked my ears and slapped me in the forehead when the teacher wasn’t looking. I dared not say anything for that would only make things worse. Not surprising, my grades didn’t improve.

Another time I was chosen to say a line in our church play. I don’t know why I let them talk me into it. It turned out to be one of the most horrific moments of my life. “The women say the tomb is empty,” was all I had to say. When it came time recite my line I walked out into the front of the church with another kid my age, all decked out in biblical period clothing. I took a deep breath and tried to force the words out. “The W-w-w-w-w-w-w-w-w-w-w-w.” was all I could manage. My lower jaw thrashed up and down as I tried to say the word “women.” I just couldn’t do it. My Sunday school teacher mouthed the words she thought I had forgotten. She didn’t get it. I knew my line. I just couldn’t say it. I tried over and over. My lower jaw quaked so violently, my teeth scraped together. Finally, I managed to get most of the words out by skipping over some of the sounds that were most difficult for me to say. If I couldn’t make the double-you sound in “woman,” I would just say “uman.” It worked and I got through it, however I’m not sure if anybody understood what I had said. My teeth and jaw ached the rest of the day. It was then that I vowed never to let anybody talk me into being in a play again and I’ve kept that vow to this day.

Occasionally, I would get a teacher who understood my situation and I would excel in the class, but most of the time teachers weren’t willing to go the extra mile or they were not observant enough to realize I had special needs. One person who saw my potential was my seventh grade science teacher. I got A’s in his class. He allowed me to give oral reports after school and didn’t call on me to answer questions out loud in class. Instead of penalizing me for non-participation, he gave me work I could do to compensate. This made me feel comfortable and more relaxed, which helped me to do well. It was also a class with more mature, intelligent students who didn’t have the need to pick on weaker kids in order to make themselves feel superior. The next year I was put into a different teacher’s class and my grades went down-hill. The school’s answer was to move me into a lower-level science class which, fortunately for me, was being taught my the same teacher I had in seventh grade. Knowing I didn’t belong there, he immediately moved me to his advanced class where I once again excelled. If only there were more people like him in my path throughout my life.

I wasn’t overlooked by everybody. The school’s answer to my problem was speech therapy. Once or twice a week I was taken out of class and led to a tiny room near the front offices. There I had one-on-one sessions with a speech therapist. I really enjoyed these sessions, though I don’t think they helped at all with my stuttering. Back then, nobody knew anything about stuttering, why it happened or how to help it. The therapists had me participate in some crazy experiments. One of which got me hooked on Bubble Yum. She would have me place two of those soft, square, delicious morsels into my mouth and chew as I read from a book. The exercise was intended to teach me to slow down when I spoke. For a half-hour, twice a week, I got to chew wads of Bubble Yum and read. It was fun. Other exercises included tapping my foot and talking with the rhythm, singing, breathing slowly, and many others I don’t even remember. None of them worked, because stuttering has nothing to do with speed, breathing, or tempo. It’s much more than a speech problem. It’s a nervous problem. One of the most elaborate inventions I was asked to try out was and electronic voice camouflager. I wore a small electronic box on my belt or in my shirt pocket which had a wire going to a sensor held against my larynx and a set of ear buds. Whenever I spoke, the device would create a loud buzzing in my ears. It’s purpose was to block out my ability to hear my own voice. It was believed that stuttering was caused by a feedback loop of hearing your own voice and this device would interrupt that loop. I tried it for a few weeks. It was terrible and it didn’t work. Nothing they tried worked.

It was one day when I was skipping school to avoid the unpleasant teasing when I crossed the road just as my speech therapist, Mr. Arnold was driving by. He knew something was wrong because school was a couple miles in the opposite direction. He pulled over and invited me to sit in his car. I had all I could do to keep from crying when he asked what I was doing. I couldn’t talk. If I did, I would cry and I didn’t want to cry in front of him. I just sat there and stared at the floor as he asked me over and over what was wrong. “I can’t help you if you don’t tell me,” he said. I couldn’t tell him. I don’t know what was so hard about saying I was being bullied, but I think it was because I was ashamed. I was ashamed of myself. I was different than everyone else and I didn’t understand why. I felt like I was a different species as I walked alone down a crowded hallway. Nobody liked me and I didn’t understand why. Perhaps I was ugly. I wasn’t good at sports and gym games. I couldn’t talk. The girls didn’t like me. I didn’t fit in anyplace. I was alone, but as long as I didn’t have to face that, things were okay. If I told anybody about my problem, I would be forced to face it. I wasn’t strong enough to do that. Mr. Arnold took me back to school and explained that I was late because I had a session with him. It was second period. I was rescued from first period gym class. That’s all that mattered.

In high-school, the first day of classes was like playing Russian roulette. Would I get teachers who understood my problem, or teachers who would not? My stomach would be in knots as I waited for the teacher to come through the door. Kids with scheduling issues and other questions would clamber up to the desk forcing me to wait until it was clear to have a private conversation about my secret issue. Sweat would bead up on my forehead and I would begin feeling sick until I had my turn to talk in private. But sometimes the teacher would order us to take our seats before I had my chance. These first day meetings were hell, but I learned quickly that teachers didn’t like dealing with difficult problems, so if I was able to talk to them quickly before the first class started on the first day of school, I could tell them about my stuttering and they wouldn’t bother with me the rest of the year. Although this tactic was successful, ironically, it was probably the most destructive thing I could have done to myself. I went through an entire four years of high-school without ever speaking out loud in class.

I always thought bullies were like chickens, unable to achieve higher thinking with their tiny brains. A chicken will peck at a weaker member of the flock until it is dead. Smarter animals nurture and help the weaker members, creating overall strength in their numbers. The stupidest chickens were so busy pecking at the weak that they would forget to watch for hawks. It feels awful to be picked on, but it feels great to see the bully get whisked away.

As far as I could tell, I was the only person in the world who stuttered. There was nobody in my family, nobody in my neighborhood, nobody in my school, and I never saw anybody on TV. I saw blind people, deaf people, people in wheel chairs, people with mental disabilities, but nobody who stuttered. I was the only one. Most people didn’t know anything about stuttering and some would say the dumbest things. I remember one man telling me stuttering was a bad habit and I should stop immediately. He didn’t understand that I had no control over it. Many people would just ignore my problem, unsure of the how to respond, however, the teasing from other kids never stopped. It was humiliating, degrading, mortifying, embarrassing, demeaning, but I always found ways to get through.

One of the easiest ways to avoid speaking out loud was to simply cut class. As soon as I saw that we had a substitute teacher I would leave the room. Sure, I would have to sit through after school detention for a few days as punishment, but that was much better than being called on in class by a teacher who did not know my problem.

My high-school speech therapist, Mr. Arnold, once referred to me as a walking thesaurus. I could always feel that I was going to #stutter before any sound came out of my mouth, so I had a split second to change what I was going to say, or not say anything at all. For example, if I feel a stutter coming on at the beginning of a thought, I would change what I was going to say completely. If I was going to say something about a car, I would change it to something about the chair I was sitting on. In the middle of a thought I could change a single word to something that meant the same thing. Sometimes I would pretend I forgot what I was going to say. These are tactics I still use to this day. I’ve become so good at it, that most people don’t even know I stutter. This works well if you’re talking on the fly, but doesn’t work at all if you are reading. You can’t change what’s in writing. In high-school, it is very common for the teacher to go around the room having the students take turns reading. To me, this was waiting my turn for the hangman’s noose.

One by one after each student read their part, the teacher would call on the next, going around the room in a torturous slow pace, each time getting one head closer to mine. My heart would race faster and faster as my turn came closer. It was terrifying. I never heard anything that was read. Inside my head sirens and alarms were screaming, “Get out now!” My hands would sweat as I tightened them into fists. My breathing would be heavy and erratic. My stomach would be ready to dispense my lunch. Finally, the kid in front of me would finish his part and it would be my turn. “What paragraph did he just read? What page are we on?” Panic would sweep over me. Then the teacher would call on the student sitting behind me, totally skipping over me. A wave of relief would flow over me as the blood drained from my bright red face. She remembered; I would think. That private conversation at the beginning of the first day of class worked. With the pressure of #speaking out in #class off, my grades began to climb and I no longer had the need to cut class.

With better grades, I was moved to classes with more mature students and the bullying eased. However, I always wondered what the other kids thought when I was skipped over while taking turns reading in class. I’m sure they thought it was strange, but I never talked to anybody, and they didn’t speak to me, so I never had to explain myself. I learned every technique in the book on avoiding people and invented some new ones. I carried all my books for the day so I didn’t have to visit my locker. I found routes through the school that were less traveled. I moved quickly and avoided eye contact. I never went into the cafeteria. Instead of eating, I sat on the floor at the end of the hallway in the back of the school until lunch period was over. I worked hard to be invisible and was pretty good at it. I never got my picture taken during my four years of #highSchool and never attended my own graduation. There is an empty square where a photo should have been above my name in the 1986 year book and the collage of graduates that hangs in the cafeteria is void of my image. I have no memory of any of the other student’s names or the teachers save for one. My photography teacher was proud to present a special award to his best student the year I graduated. I always felt bad that I wasn’t there to receive it. I made a quick getaway after he met me in the hall, trying not to give the surprise away. But as soon as I knew he was going to call me up in front of the entire school, I went home. No award was worth that humiliation.

I don’t know how I did it, but I ended up in all regents’ classes except for English. It was the only class I couldn’t do.

I remember that day I had blocked out the memory of reading my poem. What I hadn’t realized is this was happening to me far more frequently than I thought. A natural defense mechanism was kicking in to help protect me from the unpleasant experiences I faced daily. Today I find that I have no memory of any of my teachers or classmates from school. I don’t remember any of their names or faces, nor do I remember any of the events that took place aside from a few that stood out. I blocked out everything. Even today I’m terrible at remembering names and people’s faces. As soon as I hear them, I instinctively forget them.

It wasn’t until I got to college that things changed for me. I stood up in Freshman English 101 holding a paper I had written. It was my turn to give an oral report and the paper shook in my hands. I told myself that I wasn’t going to be invisible all through college. Before reading my paper, I explained to the class that I had a stuttering problem, but I wasn’t going to let it stop me from participating in class. I asked everybody to be patient with me and I went on to read my paper. I stammered a bit. Well, maybe a lot, but I got through it and each time I read or spoke out loud in class it got better.

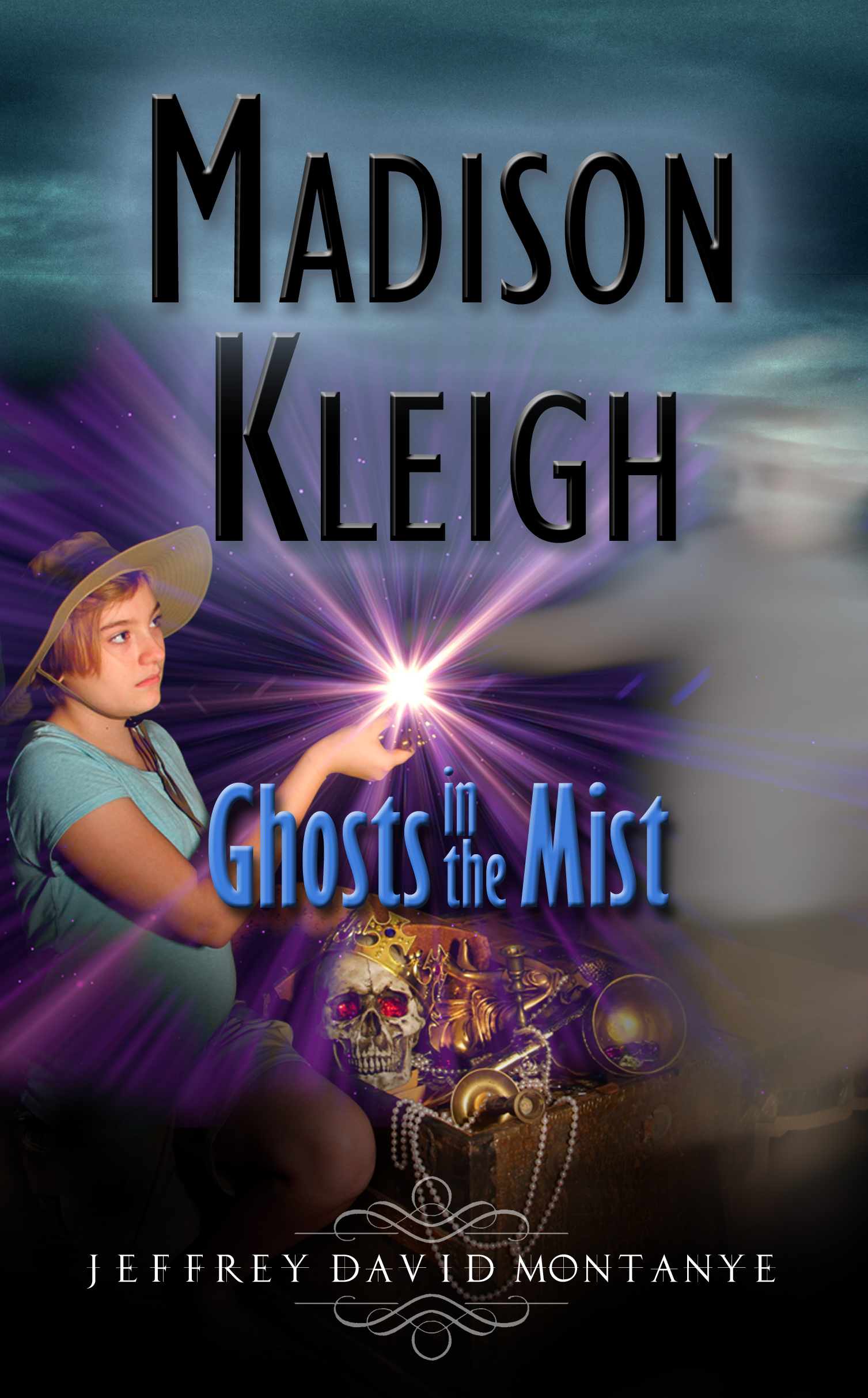

Today I teach adult enrichment classes. I frequently give talks at libraries and read stories I have written. Most people don’t know I ever had a stuttering problem. I still stammer here and there, especially when I’m excited, or tired, or anxious, but nothing like I did in school. I still struggle with the whole invisibility thing, but I’m working on it.

I’m normal now. Well, some might argue that point, however, I will never forget the pain I went through. If you asked me how I was able to beat stuttering, I would say I had to beat my emotions down. I had to stop letting things bother me. Sadness, fear, anxiety, all had to go. That is not an easy thing to do. You have to be like Mr. Spock, not getting emotional about anything.

“Jeff, you just won a million dollars in the lottery!”

“That’s nice.”

“Jeff, you’re sinking in quick sand and have only four minutes to live!”

“That’s nice.”

“Jeff, your cat was abducted by aliens and is about to be probed!”

“That’s nice.”

“Jeff, someone broke into your house and stole all your ravioli!”

“That’s nice.”

Happiness is the only emotion that doesn’t block your ability to talk. Unless you’re laughing too much. And that’s a good thing.

Story and photo by Jeffrey David Montanye

#Jeffreydmontanye

Hits: 169